Single-layer graphene oxide sheets are interesting as a flexible 2D material, with xy-dimensions variable up to a centimetre in length and a z-thickness of a single carbon atom. The presence of oxygen atoms with functional groups, such as hydroxy, epoxy, carboxylic acid, ketone, or aldehyde, provides graphene oxide (GO) with polarity. This unique property allows GO to disperse as single sheets in polar solvents like water or DMSO at low concentrations, in the absence of electrolytes or other colloidal particles.

Water-based pressure sensitive adhesives (PSAs) are typically made by emulsion polymerization using a low glass transition temperature base monomer, such as n-butyl acrylate or 2-ethyl hexylacrylate, together with a range of functional comonomers. Typically these include a high glass transition temperature comonomer, such as styrene or methyl methacrylate and monomers that can promote wetting and undergo secondary interactions such as (meth)acrylic acid.

Single-layer graphene is interesting as a flexible 2D material, with xy-dimensions variable up to a centimetre in length and a z-thickness of a single carbon atom. It conducts heat and electricity, has excellent mechanical strength, and is impermeable to gases except hydrogen gas. Its drawback: how to disperse it in a liquid. When you try to do this flexible sheets of graphene tend to stack as a result of attractive van der Waals interactions, making it virtually an impossible material to disperse as single sheets.

Labels are big business. A typical label has multiple layers: a topcoat for protection, the face stock, which contains the message in the form of text and/or images, a pressure-sensitive adhesive, and a release liner, which often has a release coating. The release liner and coating are only there to protect the label from sticking to things you do not wish it would stick to. You remove the liner when you wish to apply the label onto your substrate of choice, for example, a bottle containing a drink.

Imagine a label without a release liner and coating, imagine a label that could be activated at the moment you want it to stick to a substrate, a stick-on-demand linerless label.

BonLab has designed and developed a concept and prototype for a sustainable solution: a mesh reinforced pressure-sensitive adhesive for linerless label design. The idea was worked out by Emily Brogden and prof. dr. ir. Stefan Bon, in collaboration with UPM Raflatac Oy, a global supplier of label materials for branding and promotion, information and functional labelling (patent application: WO2023105120A1). The complete study, which was done at the University of Warwick, is now published in the new journal RSC Applied Polymers.

Watch the Talk by clicking here.

Microcapsules can be found in a range of commercial applications, including cosmetics, healthcare, agriculture, and food. The capsules serve as a storage vessel for an active ingredient, for example a nutrient or fragrance. They can have a variety of designs, the simplest form being a single internal liquid-based core surrounded by a solid shell. The chemical and physical characteristics of this shell influence the colloidal stability of capsules in formulations, dictate the permeability and mechanical robustness of the capsules, and can potentially regulate substrate adhesion. Beside storage, these features of the microcapsules are there to regulate and control release and delivery of the active compound.

A considerable part of the technologies used to produce microcapsule relies on the use of synthetic polymers that do not break down, with terrible consequences for environmental build up. One way is to make use of biocompatible and degradable plastics.

We provide an alternative solution, in that we fabricate the capsule from small molecular compounds, instead of polymers, that can crystallize.

We have a long history of making polymer dispersions to be used in waterborne coatings. The polymer colloids, or latex particles, are made by emulsion polymerization. Prof. Joe Keddie from the Physics Department at Surrey University contacted us if we were interested to help out on a bio-coatings project that needed some bespoke polymer latexes and colloidal formulations. With the term bio-coatings we mean here the coating formulation has the ability to entrap metabolically-active bacteria within the dried polymer film.

We loved the concept. In BonLab, PhD student Josh Booth optimized the synthesis of acrylic polymer latexes at approximately 40wt% solids with a monomodal particle size distributions. Important was to use bacteria-friendly surfactants in the semi-batch emulsion polymerization processes. Important was also to have a dry glass transition temperature of the polymer latex binder around 34 ℃, so that film formation could occur at temperatures which preserved viability of the bacteria.

The latexes were formulated as mixtures with halloysite nanoclay (hollow tubes) and E coli bacteria back at Surrey. The tubular clay was introduced to create porosity inside the polymer nanocomposite films. The overall composition of the waterborne formulation was optimized for mechanical and bacterial performance.

Emulsion polymerization is of pivotal importance as a route to the fabrication of water-based synthetic polymer colloids. The product is often referred to as a polymer latex and plays a crucial role in a wide variety of applications spanning coatings (protective/decorative/automotive), adhesives (pressure sensitive/laminating/construction), paper and inks, gloves and condoms, carpets, non-wovens, leather, asphalt paving, redispersible powders, and as plastic material modifiers.

Since its discovery in the 1920s the emulsion polymerization process and its mechanistic understanding has evolved. Our most noticeable past contributions include the first reversible-deactivation nitroxide-mediated radical emulsion polymerization (Macromolecules 1997: DOI 10.1021/ma961003s), and the development and mechanistic understanding of Pickering mini-emulsion (Macromolecules 2005: DOI 10.1021/ma051070z) and emulsion polymerization processes (J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008: DOI 10.1021/ja807242k). The latest on nano-silica stabilized Pickering Emulsion Polymerization from our lab can be found here.

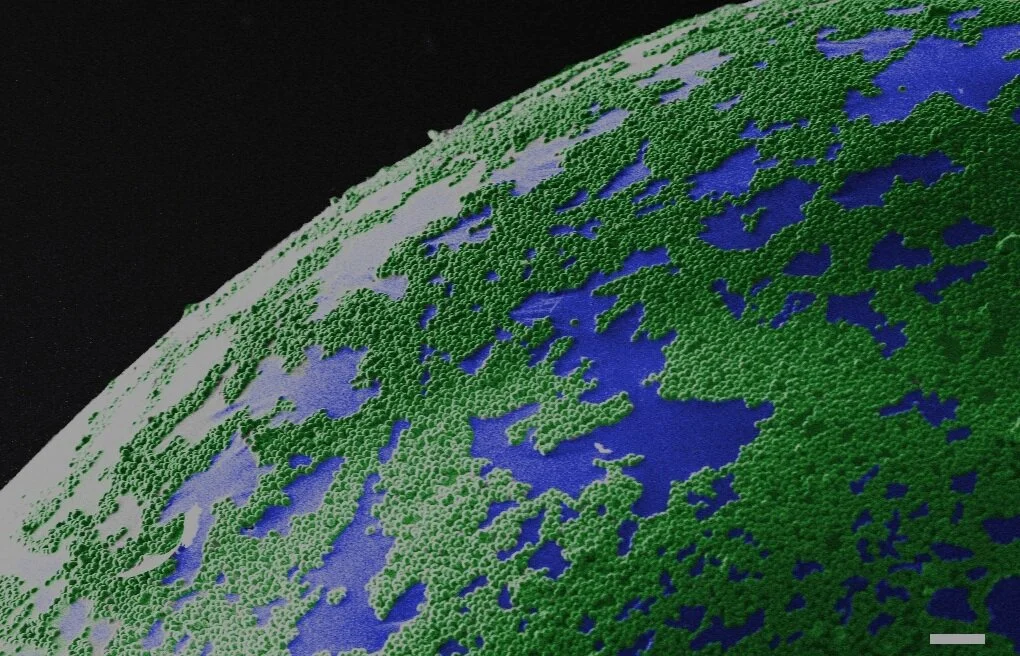

One quest in emulsion polymerization technology that remains challenging and intriguing is control of the particle morphology. It is of importance as the architecture of the polymer colloid influences its behavioural properties when used in applications. We now report in ACS Nano an elegant innovation in the emulsion polymerization process which makes use of nanogels as stabilizers and allows us to fabricate Janus and patchy polymer colloids.

Porous materials that have an interconnected network of pores are an interesting class of materials and have drawn attention in the area of separation science. The ability to fabricate robust so-called open cellular materials with control of the porosity remains a scientific challenge. The ability of regulating the interconnected network determines how a fluid (liquid or gas) can flow through the system. Think for example of how water runs through soil, or how water can be taken up through capillary action into a sponge. In addition, one can foresee that matter which flows through the porous material can temporarily be adhered/adsorbed onto the surface of the porous monolithic structure. The ability to easily control the surface functionality of the walls of the pores therefore is important.

In collaborative work with Chris Desire, a talented PhD student from the group of prof. Emily Hilder at the University of South Australia, we in the BonLab describe in Green Chemistry that we can use polymer latex particles as colloidal building blocks to form robust open cellular porous monolithic materials by simply stacking them onto each other. This assembly process is triggered by colloidal instability of a polymer latex dispersed in water which leads to the formation of a colloidal gel. The structure of the gel can then be made permanent by cross-linking through polymerization.

Emulsion polymerization is an important industrial production method to prepare latexes. Polymer latex particles are typically 40-1000 nm and dispersed in water. The polymer dispersions find application in wide ranges of products, such as coatings and adhesives, gloves and condoms, paper textiles and carpets, concrete reinforcement, and so on.

Conventional emulsion polymerization processes make use of molecular surfactants, which aids the polymerization reaction during which the particles are made and keeps the polymer colloids dispersed in water. We, and others, introduced Pickering emulsion polymerization a decade ago in which we replace common surfactants with inorganic nanoparticles.

In Pickering emulsion polymerization the polymer particles made are covered with an armor of the inorganic nanoparticles. This offers a nanocomposite colloid which may have intriguing properties and features not present in conventional "naked" polymer latexes.

To fully exploit this innovation in emulsion polymers, a mechanistic understanding of the polymerization process is essential. Current understanding is limited which restricts the use of the technique in the fabrication of more complex, multilayered colloids.

Polymer latex particles, typically 50-600 nm in diameter, are used in many applications, such as paper manufacturing, water-based adhesives, printing, and coatings. Commonly, a water-based formulation that contains these polymer colloids is used, often together with other components, such as pigments for opacity and color, fillers, and rheology modifiers. Each of the polymer latex particles consists of many individual polymer chains. These water-based dispersions are applied onto a substrate as a droplet or a film, after which these systems are dried. Upon evaporation of water, the individual components will pack closely. When little water remains in between, a so-called capillary under-pressure facilitates tight packing, and if the polymer latex particles are soft, it deforms them. The last stage of the film formation process is when polymer chains from one latex particle now diffuse into a neighboring latex particle and the other way around. This process ensures that the dried film has good adhesive and mechanical properties.

Visualizing this drying and film formation process in real time would greatly help in understanding how the properties of a dried film come about. In our paper, published in the American Chemical Society’s journal Langmuir, we used TeraHertz Time-Domain Spectroscopy (THz-TDS) to map the water content spatially in real-time during the drying process.