Water-based pressure sensitive adhesives (PSAs) are typically made by emulsion polymerization using a low glass transition temperature base monomer, such as n-butyl acrylate or 2-ethyl hexylacrylate, together with a range of functional comonomers. Typically these include a high glass transition temperature comonomer, such as styrene or methyl methacrylate and monomers that can promote wetting and undergo secondary interactions such as (meth)acrylic acid.

Labels are big business. A typical label has multiple layers: a topcoat for protection, the face stock, which contains the message in the form of text and/or images, a pressure-sensitive adhesive, and a release liner, which often has a release coating. The release liner and coating are only there to protect the label from sticking to things you do not wish it would stick to. You remove the liner when you wish to apply the label onto your substrate of choice, for example, a bottle containing a drink.

Imagine a label without a release liner and coating, imagine a label that could be activated at the moment you want it to stick to a substrate, a stick-on-demand linerless label.

BonLab has designed and developed a concept and prototype for a sustainable solution: a mesh reinforced pressure-sensitive adhesive for linerless label design. The idea was worked out by Emily Brogden and prof. dr. ir. Stefan Bon, in collaboration with UPM Raflatac Oy, a global supplier of label materials for branding and promotion, information and functional labelling (patent application: WO2023105120A1). The complete study, which was done at the University of Warwick, is now published in the new journal RSC Applied Polymers.

We set out to develop a prototype for “icy road” warning signs which was able to operate autonomously without the use of electricity, and which could be easily placed onto existing road features, such as street boundary pillars and road safety barriers.

The number of road accidents in the UK under frosty or icy conditions runs in the thousands. Our concept would aid to reduce these numbers, without the introduction of a digital, and thus electric, infrastructure.

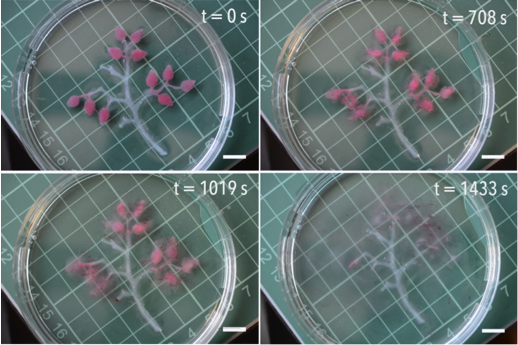

The results from our studies are now published open access in the Journal of Materials Chemistry C from the Royal Society of Chemistry. The conceptual road sign application is a multi-lamellar flexible strip.

A temperature triggered response in the form of an upper critical solution temperature (UCST) type phase separation targeted near the freezing point of water manifests itself through light scattering as a clear-to-opaque transition. It is simultaneously amplified by an enhanced photoluminescence effect.

A fresh lick of paint breathes new life into a tired looking place. Ever wondered how a thin layer of paint is so effective in hiding what lies underneath from vision? Beside colour pigments, and a binder that makes it stick, paints contain microscopic particles that are great at scattering light and turning that thin layer of paint opaque. The golden standard for these opacifiers are small titanium dioxide particles, of dimensions considerably smaller than one micron. Their use is not without controversy, as they are a big environmental burden, with a large carbon footprint and a questionable impact on human health. The reason why titanium dioxide particles are great at scattering light is that they have a high refractive index compared to the other paint ingredients, so when distributed throughout the dried paint film their hiding power of the underlying surface is fantastic. When no coloured pigments are used, the coated surface appears then whiter than white.

Ideally though, titanium dioxide should be replaced, but the list of safe high refractive materials is very limited. This makes you wonder if there is another handle, beside refractive index? Can we design efficient scattering enhancers from materials of lower refractive index?. Inspiration came from the white Cyphochilus beetle, native to southeast Asia. The scales of the beetle are not made of high refractive index materials, but they thank their white appearance to an intricate anisotropic porous microstructure, resembling the bare branches of a dense bush.

Watch the Talk by clicking here.

Microcapsules can be found in a range of commercial applications, including cosmetics, healthcare, agriculture, and food. The capsules serve as a storage vessel for an active ingredient, for example a nutrient or fragrance. They can have a variety of designs, the simplest form being a single internal liquid-based core surrounded by a solid shell. The chemical and physical characteristics of this shell influence the colloidal stability of capsules in formulations, dictate the permeability and mechanical robustness of the capsules, and can potentially regulate substrate adhesion. Beside storage, these features of the microcapsules are there to regulate and control release and delivery of the active compound.

A considerable part of the technologies used to produce microcapsule relies on the use of synthetic polymers that do not break down, with terrible consequences for environmental build up. One way is to make use of biocompatible and degradable plastics.

We provide an alternative solution, in that we fabricate the capsule from small molecular compounds, instead of polymers, that can crystallize.

A hydrogel is a solid object predominantly composed of water. The water is held together by a cross-linked 3D mesh, which is formed from components such as polymer molecules or colloidal particles. Hydrogels can be found in a wide range of application areas, for example food (think of agar, gelatine, tapioca, alginate containing products), and health (wound dressing, contact lenses, hygiene products, tissue engineering scaffolds, and drug delivery systems).

In Nature hydrogels can be found widely in soft organisms. Jellyfish spring to mind. These are intriguing creatures and form an inspiration for an area called soft robotics, a discipline seek to fabricate soft structures capable of adaptation, ultimately superseding mechanical hard-robots. Hydrogels are an ideal building block for the design of soft robots as their material characteristics can be tailored. It is however, challenging to introduce and program responsive autonomous behaviour and complex functions into man-made hydrogel objects.

Ross Jaggers and prof.dr.ir. Stefan Bon at BonLab have now developed technology that allows for temporal and spatial programming of hydrogel objects, which we made from the biopolymer sodium alginate. Key to its design was the combined use of enzyme and metal-chelation know-how.

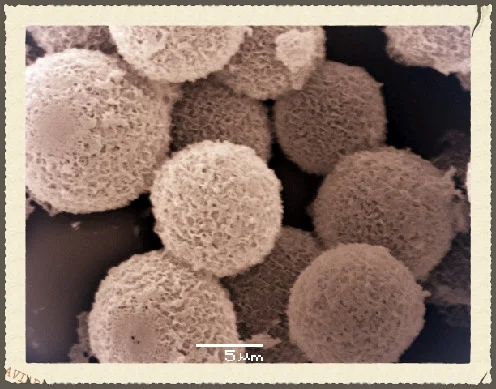

Calcium phosphate based hybrid materials are of great interest for bio-related science, for example our bones and teeth contain mineral components made from calcium phosphate. One class of materials of great interest are microcapsules, as these can store and release active ingredients. Calcium phosphate microcapsules have been made before via a number of synthetic pathways. Key drawbacks however are tedious and long (up to a month) fabrication methods. In our paper published recently in the Journal of Materials Chemistry B we report on a versatile and time-efficient method to fabricate calcium phosphate (CaP) microcapsules by utilizing oil-in-water emulsion droplets stabilized with synthetic branched copolymer (BCP) as templates. The BCP was designed to provide a suitable architecture and functionality to produce stable emulsion droplets, and to permit the mineralization of CaP at the surface of the oil droplet when incubated in a solution containing calcium and phosphate ions. The CaP shells of the microcapsules were established to be calcium deficient hydroxyapatite with incorporated chlorine and carbonate species. These capsule walls were made fluorescent by decoration with a fluorescein-bisphosphonate conjugate.

To read the paper: DOI: 10.1039/C5TB00893J

Researchers at The University of Warwick have made significant progress in the search for sustainable alternatives to conventional plastics. In response to growing environmental concerns, the move towards a circular economy and changing consumer preferences, the research team has identified that certain mixtures of small organic molecules form interesting glasses and viscous liquids. These so-called organic eutectics are promising candidates for replacing polymers in various products.