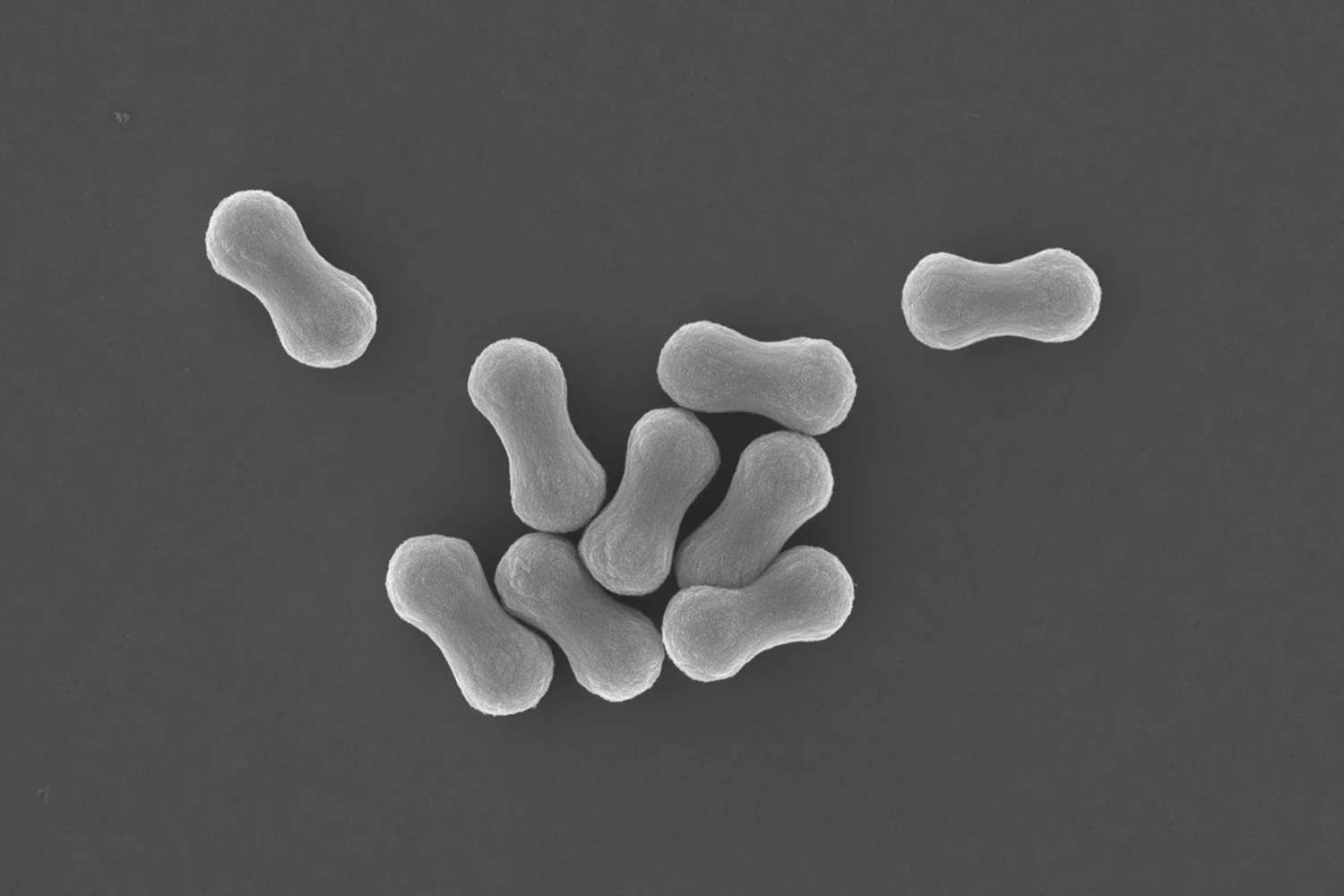

Spherical microparticles that are roughened up, so that their surfaces are no longer smooth, are intriguing. You can wonder that when we place a large number of these particles in a liquid, it may show interesting rheological behaviour. For example, would they behave like cornstarch in that when we apply a lot of shear it thickens? You can imagine that spiky spheres can interlock and jam. Biologists are interested in how microparticles interact with cells and organisms, and have started to show that the shape of the particle can play an important role. Similarly, these small particles of intricate shape may show fascinating behavior at deformable surfaces, for example is there a cheerio effect?, and may show unexpected motion. This sounds all fun, but how do we make rough microparticles, as for polymer ones this is not easy?

A mechanistic investigation of Pickering emulsion polymerization

Emulsion polymerization is an important industrial production method to prepare latexes. Polymer latex particles are typically 40-1000 nm and dispersed in water. The polymer dispersions find application in wide ranges of products, such as coatings and adhesives, gloves and condoms, paper textiles and carpets, concrete reinforcement, and so on.

Conventional emulsion polymerization processes make use of molecular surfactants, which aids the polymerization reaction during which the particles are made and keeps the polymer colloids dispersed in water. We, and others, introduced Pickering emulsion polymerization a decade ago in which we replace common surfactants with inorganic nanoparticles.

In Pickering emulsion polymerization the polymer particles made are covered with an armor of the inorganic nanoparticles. This offers a nanocomposite colloid which may have intriguing properties and features not present in conventional "naked" polymer latexes.

To fully exploit this innovation in emulsion polymers, a mechanistic understanding of the polymerization process is essential. Current understanding is limited which restricts the use of the technique in the fabrication of more complex, multilayered colloids.

Independent responsive behaviour and communication in hydrogel objects

Autonomous response mechanisms are vital to the survival of living organisms and play a key role in both biological function and independent behaviour. The design of artificial life, such as neural networks that model the human brain and robotic devices that can perform complex tasks, relies on programmed intelligence so that responses to stimuli are possible. Responsive synthetic materials can translate environmental stimuli into a direct material response, for example thermo-responsive shape change in polymer gels or light-triggered drug release from capsules. Materials that have the ability to moderate their own behaviour over time and selectively respond to their environment, however, display autonomy and more closely resemble those found in nature.